Why I Gave Up Coffee: Mind Hacks + Memories

(Editor’s Note: I am very soon turning 40. I have thoughts. I have memories. I have reason to share them. Read on…)

I recently gave up something I loved. It was something I thought I needed to function. It was something I was subtly and happily routinely dependent on.

I didn’t give it up for a religious reason or because someone confronted me about it.

I did it, as I do many things that I ponder long and hard, as a temporary experiment only.

I take this approach, I think, to trick my ego into releasing an established habit on a short-term, no commitment basis only. This little mind hack is super helpful for me because once I am committed to something I am, like, moon-landing committed. So I tend to tiptoe around commitment for a good long while, hemming and hawing, until I know either I am totally ready or I am terrified that I might not be. Either way, it’s that time when I jump.

Back to the regularly scheduled confession: For a few important reasons, about a month ago, I gave up drinking coffee.

Full disclosure: I still drink a cup of coffee once in awhile. Maybe once a week. Maybe.

But that’s it.

I used to be a 1-cup-before-I-leave-the-house, then espresso, then maybe an afternoon iced coffee sort of lady.

So it wasn’t obscene or gallon-ic level intake. It was probably modest caffeine-ism at best.

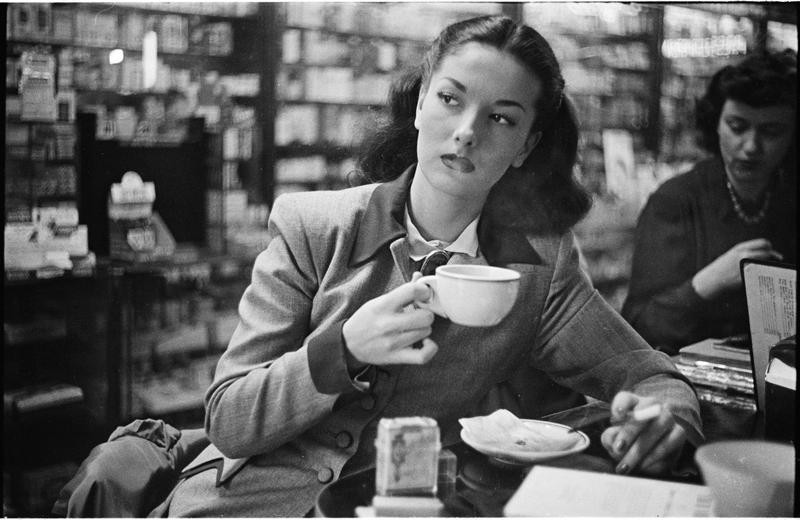

Honestly, it was the routine of this brown-eyed beverage that I loved the most. I loved the filters, the scooping, the brewing, the miracle of water into coffee dripping, the first pour, and, like many pleasures of mine — the smells. Coffee has the best roasted, earthy, rooted, caramel, smoky, tucked in scent possible.

One inhale brings me the full-bodied ideas of mornings of possibility, of standing espresso bars in Italy’s early light, of the care of another for me, of in-depth post-dinner conversations around crammed tables mostly cleared of food, of moments of reassuring sound, when all you hear is a sip and swallow and sigh.

I remember as a child, lying half asleep in my grandparent’s cool, dark basement on the sheet-covered sofa as my grandmother, up at 5 or 6 a.m., would put on the stovetop percolator coffee maker, just up the stairs. I would listen to her day beginning and feel intensely comforted. The shuffle of her slippered feet on the orange and cream-colored linoleum tile in the kitchen, the whooshing of cabinets opening and their soft close. The front door creaking as she went to fetch the paper, the tinkling of the cups being set out as the soft pop-pop-blop of the coffee perked on the stove and I drifted back off to sleep.

Coffee meant safety, home.

I recall watching my mother measuring out the coffee in the maker before guests arrived for dinner, so that all she had to do was hit the button as she cleared plates and — voila! — fresh coffee would pair with her homemade pavlova or pumpkin roll or angel food cake, to her guest’s delight and comfort. When my mother entertained, which she did regularly, her focus was always on her guests’ delight and comfort. My job in this coffee caravan was to fill and set out the cream and sugar in the delicate ceramic coffee service with the painted roses and dessert teaspoons with enamel handles. If she was totally on her game, I served sugar cubes out of a clear crimson glass sugar vase with vintage miniature silver tongs she found at an antique housewares boutique.

Coffee meant care, comfort.

I tried to like coffee on my own terms in high school and college, but I only pretended to. I drank it to stay awake to study for my AP exams, or to finish a paper. I masked my dislike of the way it hit my stomach and turned it a bit sour. I pretended being shaky after one cup was a fun feeling. I took the gateway cups and fancied them up with flavored creamers, flavored coffees, with cinnamon and raw sugars.

Then, I slowly drifted away from my consumption.

It was a secret relief.

Until 2003, when my daughter was born and coffee became pretty much the only way I was going to survive being a sleep loving, yet sleep deprived, mom of a child who only slept in 4-hour increments until she was 4. Not an exaggeration.

From then on, and throughout my time as a mom who works and raises kids full-time, coffee has been my wingman.

So why did I give it up?

There were health reasons I could have ignored. There were also the memories of shaky hands and sour stomachs that had been so keenly present when I first started drinking it.

There was the sense that I wasn’t even feeling those things anymore. Then, there was the notion, needling ever deeper into my heart, that I might not be feeling them because my mind was no longer taking my body’s phone call that coffee and I didn’t really get along. That perhaps all those symptoms were still going on, but that my mind was blocking them.

I began to wonder what it would feel like not to drink coffee. How would my body, my blood stream, my temperament respond? What if I could stop that phone from ringing from my body to my brain?

I had worked so hard to convince myself over the last 13 years that I needed it, but maybe, when it was all said and done, I didn’t.

Ultimately, that’s what made the experiment permanent.

Because the notion I couldn’t shake turned out to be right. I felt much clearer, calmer and less sour stomached without coffee. Without it, my hands didn’t shake. I felt less dizzy.

I didn’t get as snappy around mid-morning.

And I was just as alert, just as on, without it.

It was a welcome discovery.

It felt right — for me.

As I reflected on all of this, I acknowledged we were raised, more than anything else, on tea.

My mother was an avid tea drinker before my older brother married a Brit. Every single night when dinner was cleared up, she would put a kettle to boil on the stove. Warming water in the microwave for tea was always out of the question. A piping hot cuppa would accompany her to bed, perching on her stack of books, or would settle her down at the dinner table as she sewed loose buttons or reviewed someone’s final essay or sat you down to talk about your grade in math.

Tea greeted us on cold mornings beside bowls of grits or oatmeal or cream of wheat with brown sugar.

For my 8th birthday, a formal tea party was held and all the attendees wore gloves. For real.

For my mother’s 50th birthday, friends threw her a surprise birthday tea party. I was roped into bringing her to the cute cottage-like tea place for the surprise. She had no idea and was tickled to see her closest friends gathered for her. Surprising the best hostess in the group was never an easy task.

For her 61st birthday, we held a tea party for her once again.

She had just found out her cancer was on the march again. And I mean crying-in-the-car-all-the-way-there — just. None of her adoring guests, those who came in fancy dresses and ridiculous hats, knew yet that she’d just received her death sentence.

She wore one of her mother’s vintage pillbox hats with faux wild roses in pink and orange around the brim. Her hair was thin, her skin was yellowish and she was gauntly thin. But she would not cancel.

What I remember of her on that day were her wide smiles, her tears of joy, the sound of her throaty laugh, the one where she clapped her hands together in delight as she tipped back her chin and bellowed.

I remember giving her my gift — the ham-handed “MOM” child’s level cross-stitch I had made for her over the last two months — an attempt to be more of the handy daughter I thought she really wanted when I was a kid. I remember how she welled up then and I felt so deeply in my bones that this $5 token was successful at expressing something of the total devotion of love I felt for her.

I remember how all her friends fawned over her, showered her with gifts and generally made her feel as if she was the queen herself.

She loved tea. And she loved tea parties.

It was the last party we had for her that really mattered.

We all have to learn to let go of the things we think we need in this life.

When we don’t want to, when we can’t imagine ever doing it, and when we choose to and when we can.

Whether it’s coffee or tea, or a bad habit or a good friend who’s done you wrong.

Whether it’s something you use to cope with life or the someone who gave you life.

At 40, I think I’ve learned that it doesn’t matter how we let go — if we use mind hacks, denial, dextox or heart-pouring mourning.

It’s only in the letting that we go.